The taste preserved by a husband-and-wife team

Imagine the crispy texture and aroma of Nanbu wheat spreading in your mouth. The word senbei (rice crackers) may conjure images of crackers made from rice or sticky rice, but in this region, it refers to Nanbu senbei crackers made from wheat flour. This region’s cold, moist easterly winds made it unsuitable for rice cultivation in the past. Instead, flour cultivation has flourished since ancient times, and Aomori and Iwate are the main production areas of Nanbu senbei crackers. Only those using Nanbu wheat as an ingredient can officially be called Nanbu senbei crackers.

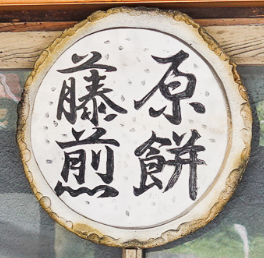

In Ninohe City, many businesses make senbei crackers with their specialties and brands. Some companies explore new possibilities, such as adding chocolate, while other small businesses preserve the simple, old-fashioned style. One is Fujiwara Senbei Shop, located near Kindaichi Onsen, established by Hidetoshi Fujiwara’s parents in 1962. They bake 500 to 600 Nanbu senbei crackers every day.

“We wake up at 5:30 a.m., start the charcoal on the stove, and fire the charcoal in the kiln around 6:30 a.m. Then we mix flour, salt, baking soda, and water to make the dough, cut it into small pieces by hand, dip them in sesame seeds, and bake them. The heat builds up, so it’s hard work in the summer,” says Hidetoshi.

He speaks with sweat on his forehead. Fujiwara Senbei Shop makes the most of the local ingredients: the flour is 100% Nanbu wheat from Iwate Prefecture, which has a rich aroma and a sweet taste, and the charcoal is from Mt. Oritsume, a famous mountain in Ninohe. The kiln has eight rows of four iron molds fired by turning a handle on the side. Unlike gas grills, charcoal grills are challenging to maintain a constant temperature, and since they cannot put out the fire once it’s started, all the rice crackers are baked right away in the morning.

According to Hidetoshi, each household had a round cast-iron mold press in the old days, and mothers used to make Nanbu senbei crackers for their families. There is a deep history of ironware production due to the abundance of high-quality materials such as iron sand. Nanbu ironware is a part of daily life in Iwate.

In the past, farmers brought Nanbu senbei crackers to work and used them as plates when eating side dishes such as pickles for lunch. The crackers drizzled with starch syrup were enjoyed as snacks between farm work. During festivals and celebrations, they were used as a plate to eat sekihan (red rice). After absorbing steam, the crackers became soft and fluffy, which was another delicious way to eat them. People in this area continue to eat crackers very often.

Hitoshi explains, “Some young people like putting cheese on their crackers and eating it like a pizza. Customers who buy crackers weekly say, ‘If this shop closes down, we would have trouble getting snacks,’ so I have to keep working hard.”

There is a wide variety of flavors for Nanbu senbei crackers, and even the same simple cracker has different tastes according to the blend of wheat. Each of the locals has various recommendations, and it is tempting to get them all and compare them.

Hidetoshi hands a freshly baked cracker. The charcoal fire gives it a unique aroma and a crunchy texture, and the more you bite into it, the more the flavor spreads. It is filled with the simple and nostalgic taste of home cooking the couple wants to preserve.